Adjoints

Not-so-complex multiplication - An Introductory Challenge related to CM theory

For KalmarCTF 2025 I authored two challenges - one quite hard and one quite easy. This blogpost covers the easier one - Not-so-complex multiplication.

The goal of this challenge was to make a challenge that was almost trivial if you know about how abit about how the trace of frobenius, the order of a curve, and good reduction of CM-curves (over $\mathbb{Q}$) all relate (this is all part of the so-called "complex multiplication-theory"). Unfortunately, it turned out to be a bit too easy even if you don't have a clue what any of these things mean.

Nevertheless, I'll include a short writeup. I've also written a short explenation of what going on towards the end of this post, if you are still curious about that :)

The challenge and solution

The challenge description reads

It's dangerous to go alone! Take this: https://www.lmfdb.org/EllipticCurve/Q/

Pointing to the LMFDB, a big database full of elliptic curves and related things. We download the challenge file, which reads

from sage.all import *

FLAG = b"kalmar{???}"

# Generate secret primes of the form x^2 + 7y^2

ps = []

x = randint(0, 2**100)

while gcd(x, 7) > 1:

x = randint(0, 2**100)

while len(ps) < 10:

pi = x**2 + 7*randint(0, 2**100)**2

if is_prime(pi):

ps.append(pi)

for p in ps:

F = GF(p)

E = EllipticCurve_from_j(F(int("ff", 16))**3)

print(E.order())

print(sum(ps))

# Encrypt the flag

import hashlib

import os

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Util.Padding import pad, unpad

def encrypt_flag(secret: int):

sha1 = hashlib.sha1()

sha1.update(str(secret).encode('ascii'))

key = sha1.digest()[:16]

iv = os.urandom(16)

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv)

ciphertext = cipher.encrypt(pad(FLAG, 16))

return iv.hex(), ciphertext.hex()

# Good luck! :^)

print(encrypt_flag(prod(ps)))

The challenge is thus to recover the product of ten secret primes $p_i$, given the following information:

- The primes are all of the form $p_i = x^2 + 7y_i^2$.

- The order of a curve with $j$-invariant $255^3$ over $\mathbb{F}_{p_i}$.

- The sum of the $p_i$'s.

Unfortunately, the challenge is maybe too easy, as on can can run a simple example one self, and in the loop also print p and x. Then its immidiately obvious that

$$

p_i + 1 - \#E(\mathbb{F}_{p_i}) = \pm 2x

$$

These give 10 equations in 11 unknowns (the $p_i$'s and $x$), but we also know the sum of the $p_i$'s, thus solving a simple linear system of equations gives the solution (note that we have to guess all the possible signs of $2x$ in every equation, but this provides little challenge).

Full solve:

from sage.all import *

from ast import literal_eval

sol_vec = []

with open("output.txt", "r") as f:

for i, line in enumerate(f.readlines()):

if i == 11:

enc = literal_eval(line)

iv = enc[0]

ct = enc[1]

break

if i == 10:

sol_vec.append(Integer(line))

else:

sol_vec.append(Integer(line) - 1)

from itertools import product

k = 10

for bla in product([1, -1], repeat=k):

System = []

for i in range(k):

row = [0 for _ in range(k+1)]

row[0] = bla[i]

row[i+1] = 1

System.append(row)

last_row = [1 for _ in range(k+1)]

last_row[0] = 0

System.append(last_row)

try:

sol = Matrix(System).solve_right(vector(sol_vec))

except:

continue

if all(ell in ZZ for ell in sol):

if all([is_pseudoprime(ell) for ell in sol[1:]]):

print("GOT IT!")

print(sol)

break

import hashlib

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Util.Padding import pad, unpad

sha1 = hashlib.sha1()

sha1.update(str(prod(sol[1:])).encode('ascii'))

key = sha1.digest()[:16]

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, bytes.fromhex(iv))

print(unpad(cipher.decrypt(bytes.fromhex(ct)), 16))

Which gives the flag

kalmar{C0mpl3x_mult1pl1c4ti0n?_M0re_l1k3_e4sy_mult1pl1c4t10n_h4ha_gott3m}

What's going on?

Although we could get the flag without really understanding what happened, it seems very curious that the orders of these curves are so predictable? Lets look at what is really happening here.

Reduction of a CM-curve

First we recall that the endomorphism ring of an elliptic curve $E$ can be either:

- $\mathbb{Z}$

- An imaginary quadratic order (i.e. something of the form $\mathbb{Z}[\frac{1+\sqrt{-n}}{2}]$ or $\mathbb{Z}[\sqrt{-n}]$)

- A maximal order in a quaternion algebra.

Further, over $\mathbb{Q}$ only the first two can happen, while over finite fields, only the last two happens. A "CM-curve" is simply a curve whose endomorphism ring is one of the two last (although some authors reserve the name "CM-curve" for fields of characteristic 0, since every curve is a CM-curve in positive characteristic).

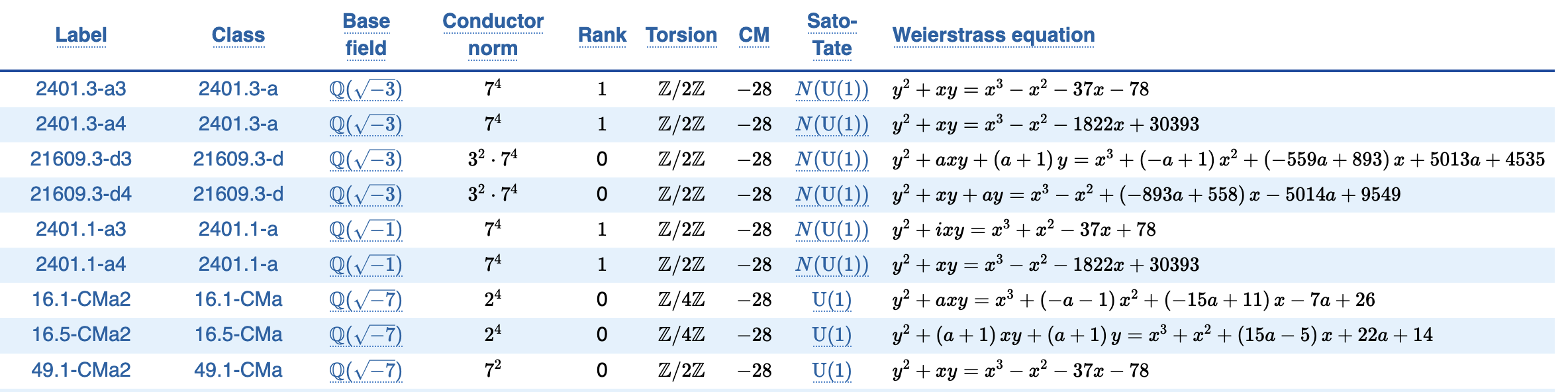

Okay, now lets start by checking out the $j$-invariant in the LMFDB:

Looking at the CM column, we see that all these curves with that $j$-invariant have CM by $-28$. Possibly looking up some definitions, we see that this means that their endomorphism ring is isomorphic to $\mathbb{Z}[\sqrt{-7}]$ (the quadratic order with discriminant $-28$). In fact, the $j$-invariant $255^3$ turns out to be the unique (!) $j$-invariant giving curves with CM by $-28$.

One fact now which is useful is that if we take one of these curves (over $\mathbb{Q}$) and reduce over a finite field $\mathbb{F}_p$ (with good reduction, i.e. the reduced curve is not singular), we still have $\mathbb{Z}[\sqrt{-7}]$ sitting inside the endomorphism ring (i.e. the endomorphism ring can become bigger, but not smaller.)

The trace of Frobenius

On $E/\mathbb{F}_p$ there is a very special endomorphism called the frobenius, defined by $$ \pi((x, y)) = (x^p, y^p). $$ In fact, $\pi$ and its dual isogeny $\widehat{\pi}$ (called the Verschiebung) are the only isogenies of degree $p$ (up to composition with isomorphisms), and its easy to see that this is an endomorphism precicely when $E$ is defined over $\mathbb{F}_p$. In this case, $\pi$ always satisfies a quadratic equation (this follows from the possible endomorphism rings) of the form $$ \pi^2 - [t]\pi + [p] = 0, $$ where $t$ is the "trace of frobenius". It is well known that this $t$ determines the order via the equation $$ \#E(\mathbb{F}_p) = p + 1 - t. $$

For a short explenation of this: One can convince oneself that $E(\mathbb{F}_p)$ is exactly $\mathrm{ker}(\pi - [1])$ (i.e. the points fixed by frobenius.) If one is willing to accept that the size of this kernel is equal to the norm of $\pi - [1]$, we simply need to compute this norm:

$$ \#E(\mathbb{F}_p) = n(\pi - 1) = (\pi - 1)\overline{(\pi - 1)} = \pi\overline{\pi} - (\pi + \overline{\pi}) + 1 = p - t + 1. $$

Relating the previous two sections

So how can we relate the previous two to explain what is going on? Well two more useful facts:

- An element $x + \sqrt{-n}y \in \mathbb{Z}[\sqrt{-n}]$ has a norm $x^2 + ny^2$ and trace $2x$.

- For CM-curves, the norm equals the degree of the corresponding endomorphism.

So, for each of our curves $E/\mathbb{F}_{p_i}$, we know that at least every element of $\mathbb{Z}[\sqrt{-7}]$ corresponds to an endomorphism of the form $[a] + \iota \circ [b]$, where $\iota^2 = [-7]$. (a priori there might be more endomorphisms, but in our case it turns out that its the whole thing every time). Thus, since the primes where chosen such that $p_i = x^2 + 7y_i^2$, we know that there exists endomorphisms of degree $p$ of the form $[\pm x] + \iota \circ [\pm y_i]$. But by the previous section, the only isogenies of degree $p_i$ were $\pm \pi_i, \pm \widehat{\pi}_i$! Hence we know that $$\pi_i = [\pm x] + \iota \circ [\pm y_i]$$

and thus we can simply read of the trace as $\pm 2x$ every time, which in turn is exactly the quantity $p_i + 1 - \#E(\mathbb{F}_{p_i})$ from before.

Conclusion

It seems like challenges using CM are always very hard (like my favorite f*cktoring). I wanted to make one that was easier, but still uses CM theory. Unfortunately, while CM theory was necessary to make the challenge, it was not really necessary to solve it. So the search for an easy CM-challenge continues...